Why we need to be concerned about the DNA Bill

The DNA Bill is drowning in vagueness as it seeks to create a database of our DNA that makes us vulnerable to attacks and must be fought.

Before every session, Parliament provides a list of government matters that are expected to be taken up to inform both the opposition and the citizens of the republic about its agenda.

In this list for the Monsoon session, the DNA Technology Regulation (Use and Application) Bill, 2019 was included for consideration and passage in the Lok Sabha. This Bill was introduced in its current form in August 2019 in the Lok Sabha. It was subsequently referred to the Standing Committee of Parliament in October 2019, which submitted its report in February this year. Surprisingly, two members of the Standing Committee (Shri Asaduddin Owaisi, Lok Sabha MP and Shri Binoy Viswam, Rajya Sabha MP) submitted dissenting notes articulating the lacunae in the Bill that the Standing Committee failed to address.

The stated objective of the Bill is to regulate the use of DNA to identify victims, offenders, suspects, accused, missing persons and unknown deceased persons. The category of “suspect” is not defined either in the Bill or in the Indian legal system. This ambiguity in the very meaning of “suspect” allows for an arbitrary action by the State giving it a free hand to collect DNA from anyone the State considers to be a suspect. There is no limit to all suspects and without a definition, anyone under the sun can be considered as such.

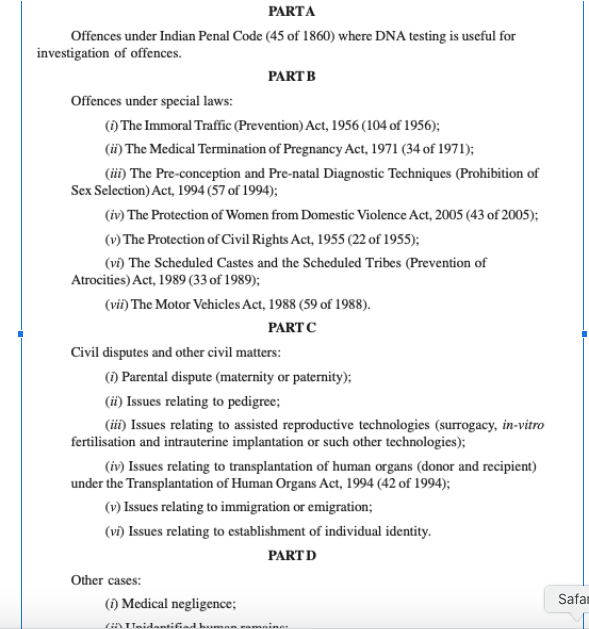

Apart from this comprehensive definition of suspects, the comprehensive nature of this Bill can be understood from the list of matters for which DNA collection/regulation/storage can be used:

As is evident, DNA testing, collection and storage are not limited to criminal matters only. They extend to a wide range of matters that even DNA experts cannot tell us how DNA will be useful in these matters such as Immoral Traffic Act, Prenatal Diagnosis Act, Motor Vehicle Act, medical negligence and issues related to assisted reproductive technology.

The use of DNA for civil matters such as “issues related to pedigree, immigration and emigration, establishment of individual identity” indicates the clear intentions of the State. As Dr Usha Ramanathan puts it, these are political categories and not legal categories. This Bill is an attempt to make these political categories definitive. We must keep in mind the recent Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 and the NRC process to understand these political categories.

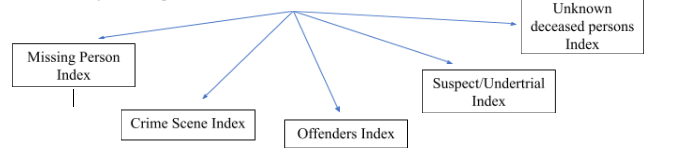

Regardless of the civil, criminal or other matters for which DNA is collected, the bills envision multiple indices, as follows:

These indices serve to create a profile of each individual whose DNA is collected and store it in the National DNA Data Bank or the Regional Data Bank. While this data must be kept by the aforementioned data banks established by the bill, it also requires private testing laboratories to keep records of information from tests performed and send them to the National or Regional Data Bank. The time period for which data profiling individual identities can be stored in these indices is not specified. In effect, it is intended to create a database with our DNA, our names, our identities revealed, as a timeless database without an established personal data protection framework.

The bill has a “conditional consent” clause for DNA being collected for the database. Under this clause, in the case of crimes with sentences of less than 7 years, a person may refuse to provide his or her DNA. But in the case of offences with sentences of more than 7 years, even if consent is withheld, the magistrate can order DNA collection. This obligation to hand over our DNA to be entered into a database where it can probably remain forever is an attack on our dignity. You and I, once our DNA is collected and stored in the database, will have no recourse to have it removed from there. And we will have no knowledge of the manner in which our DNA will be used, as there is no clause limiting the use of DNA. There is even a possibility that this database will be linked to Aadhar, given the State’s obsession with it.

DNA, as we see, is personal health information that the State has set out to collect and store. The DNA Bill, by design, is aimed at profiling people. It is a concerted attack on the fundamental right to privacy that encompasses at least three aspects: (i) intrusion into a person’s physical body, (ii) informational privacy, and (iii) privacy of choice. The DNA Bill has completely ignored all three aspects of privacy.

With the Air India, Big Basket and Dominoes data breaches resulting in the exposure of even the email addresses and passwords of government officials, this collection of health data of individuals without strict protections of the DNA data itself must be considered a threat to national security. The State does not have the ability to protect this data.

The current criminal justice system makes use of fingerprint testing and DNA testing. The Bills Statement of Objects identifies some of the challenges of using DNA for trials such as delay, need for experts to interpret DNA evidence, and yet the Bill fails to address these very challenges which it cited as one of the reasons for this Bill. In the UK, despite the collection of DNA, they have failed to establish any reduction in crime rates due to the use of DNA technology. Such a database does not help solve crime or increase the efficiency of prosecution as is abundantly evident in the UK. Even with this knowledge, the state expenditure of 20 crore as one-time cost and 5 crore as recurring cost of public money is not necessary nor in our best interest as people. Under the pretext of improving the criminal justice system by regulating DNA technology, the state is trying to bring in another legislation to profile and target individuals for political purposes. There is absolutely no compelling need on the part of the state to create such an extensive DNA database.

The DNA Bill is mired in vagueness as it seeks to create a database of our DNA that will make us vulnerable to attacks and we must oppose it.

0 Comment